Photo: Wikipedia / Tobias Klenze / CC-BY-SA 4.0 (the image has been cropped to landscape format).

Claudio Guarnieri is a software developer and security researcher, investigating the use of technology as a mean for repression, and provides assistance to human rights organizations, journalists, and activists with issues of computer security, privacy and surveillance. He is Head of Security Lab at Amnesty International, a core member of The Honeynet Project and a co-founder of Security Without Borders. Claudio is an opinion writer and columnist, published by Die Zeit, Slate, Deutsche Welle and Motherboard. He has been selected among the 50 persons of the year 2014 by Wired Italy, among the “30 Under 30” honorees for 2016 by Forbes and collected with the Citizen Lab the EFF Pioneer Award 2015.

Claudio is also an artist, engaging with issues of privacy, surveillance, and the digitization of modern society. His work “Radio Atlas” (2020) would have been part of the “Practicing Sovereignty” exhibition and symposium, where Claudio would have been an invited speaker as well. Due to the current crisis, however, this event had to be cancelled. Thus, we are grateful that Claudio gave us the opportunity to learn more about his work, especially his current analysis and artistic application of contact tracing technology, via video call.

The talk took place on May 14, 2020 and was organized as an extension of the seminar “DenkSysteme” by Daniel Irrgang (Weizenbaum Institute’s research group “Inequality and Digital Sovereignty”) and Klaus Gasteier (UdK Berlin, Institute for time-based media), while several students joined the Q&A. It is here published in a transcribed and slightly edited form. In the meantime, following the rapid pace of the pandemic crisis, a lot has happened in terms of contact tracing. Since June 15, 2020 the German contact tracing app, applying Bluetooth technology as discussed by Claudio, is now ready for download. Two days earlier, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung released an article reporting on the results of researchers at Universities in Darmstadt, Marburg and Würzburg confirming security gaps which come with the Google/Apple protocol (GAP). Until this point, those security concerns where only discussed in theory – also by Claudio. In fact, by manipulating Bluetooth data, attackers may generate movement profiles or incorrect contact information provided by those apps. And while Norway in fact, as discussed as a possibility in Claudio’s talk, has now ended its tracing app over security concerns, Kuwait and Bahrain have rolled out highly invasive contact tracing technologies, fulfilling some of the alerting predictions raised by the Amnesty International Security Lab and other organizations. We hope that this publication of the transcription of Claudio’s talk and the following Q&A will contribute to a critical discourse on digital contact tracing. In the scope of our research on inequality and digital sovereignty, we would like to use this opportunity to share the position of Amnesty International, published by Claudio on June 17, 2020: “Amnesty is demanding governments to be transparent about their plans. COVID-19 contact tracing apps should remain voluntary, free from incentives and penalties. We are not only concerned about the potentially unnecessary invasive designs of some of these apps, but also of potential discriminatory practices that could stem from an inequitable access to healthcare if these apps become too central to government’s response to the pandemic.”

Thanks a lot for inviting me. It’s a pleasure to have this opportunity to talk about some current issues. My name is Claudio. I’m originally from Italy and am living in Berlin for two years now. I am working at Amnesty International since about four years, although we’ve been collaborating for a little bit longer. I have a small team here that we call the Security Lab, where we work on anything that has to do with privacy and surveillance, specifically in relation to how these issues impact human rights and human rights defenders. So most of my work at Amnesty International revolves around researching the uses of technology in this particular context – how human rights defenders are monitored online, how technology is used to intimidate, to control, to surveil, to threaten people. That’s the essence of the work that we do, along with generally supporting all of these different individuals and small groups that we work with whenever it comes to digital security and related issues.

On the side, I double into art occasionally. I’ve always been interested in using art as a means to tell stories. Especially when it comes to digital media from an artistic approach, I always ended up working on projects describing and revealing technologies and aspects of technological society that are either meant to be invisible, meant to be unknown, or that are largely misunderstood or unknown to the general public. Just to run through a few projects: One I did a few years ago is called “Focal Opacity“ (2017). This was in a moment where there was a lot of discussion in the media about the dark web and the deep web and all of these unlimited networks and how they were being used generally in a negative and ominous way. So I did this project that was basically a live interactive system that would have the viewer automatically navigate through thousands and thousands of websites hosted in the dark web. And provide both a visual, aesthetic perspective of how these websites look like and what their general content is, as well as demystifying some of the common myths behind the dark web back then. The narrative was always focussed around the misuses and the negative uses of it, while the reality, as it came out through this project, was a lot more variegated.

I did another project which I called “Dear Machine” (2017), which similarly tried to highlight something that is not necessarily known to people. I wrote a software that was basically trying to harvest as much data from publicly available websites as possible, and it crawled hundreds of thousands of websites in the internet. Then it extracted HTML comments from all of them. With websites, generally, we see what the designers want us to see. But there are other details hidden in there. And among those are just comments the developers leave in the code of the web pages that are somewhat of a dialogue between the developer and the machine, the developer and the browser and the website itself. The software was harvesting all of these comments from web pages and then displayed it in an online installation which was typing it as it was someone writing a diary to their own machine. It was interesting to see what people leave behind in all of these comments.

I did another project some years ago, working on data sets that I collected during my work at Amnesty International. “Gallery of Surveillance” (2018/19) creates an audio-visual experience of the different types of surveillance software that we saw used against human rights defenders. Those are complex pieces of malware, often developed by commercial companies and used regularly to spy on activists or journalists. They are meant to be these invisible pieces of technology, which are designed to not to be found for as long as possible. And it has always been difficult for us to communicate and show people how these things actually look like, by virtue of the fact that this is hidden spy software. So I made this visualization and sonification of these applications in order to reverse the hidden properties of such technologies.

And then, more recently, I’ve been doing this project, “Radio Atlas” (2020), that was supposed to be up at the exhibition at Weizenbaum Institute, which now coincidentally became quite useful for me – and topical, given the current developments in contact tracing which I’m currently getting into. But originally, I was interested in radio communications as a kind of unexplored space, where electronic devices, mostly unknown to the public, continuously communicate and tell things about ourselves, about where we are and what we’re doing. This project was harvesting radio communications around a sensor. And these radio communications included devices that are looking for WiFi networks that are familiar to them, mobile phones connecting to cell towers in the neighbourhood as well as phones offering access over Bluetooth to neighbouring devices. So I harvested all of these different types of communications and created a live visualization that would show what is the radio activity around us – and what it actually tells about us.

As mentioned, it became accidentally topical, because now, with all of the conversations we’re having around COVID-19 and contact tracing and the role of technology in dealing with the pandemic, radio communications somewhat came back, especially in the form of Bluetooth, as I will go into detail in a few minutes with regards to contact tracing, which is something I’m currently looking into quite closely at work as well. Because of the fact that it’s such an imminent and widespread technology that is currently being rolled out globally to large masses of populations. At Amnesty International we are looking at it with a critical eye, to see how these technologies could potentially negatively impact human rights in different forms – the right to privacy, the right to freedom of expression, freedom of association and so on. So I’ve been spending quite some time doing these investigations into the different solutions that are currently being built. And here we are, essentially a few weeks into the pandemic, and contact tracing is, as I am stating in my blog post, is really upon us. In European countries and even more so in other countries around the world where digital contact tracing solutions have already been rolled out and are already being utilized.

So the bottom line for those that are not familiar with contact tracing is essentially this: There’s obviously a strong pressure on governments to act upon the pandemic, to control the spread of the virus and at the same time to ease the containment measures that are currently in place, that limit people’s ability to move and to work. Contact tracing is one aspect of it. In most countries, there is an ongoing push to try to find a digitalized solution to this, which in theory would allow the authorities to be able to contain the spread of the virus by monitoring how it contracts from one person to the next and by finding technological means to reconstruct where infections are going. Essentially, the problem is that in order to do contact tracing, according to most epidemiologists, digital solutions need to be able to identify contacts between individuals that are exposed to each other, in close proximity, so below 1.5 meters typically, for at least 15 minutes. And in order for this to be statistically relevant at a national scale, there needs to be a certain penetration of these apps. Usually, they’re speaking about hitting a target of 60% of the population using a national contact tracing solution. [Editor’s note: As Claudio has pointed out during the editing of this text, in the meantime, research has shown that in fact even a lower adoption rate considerably slows down the spread of the virus.]

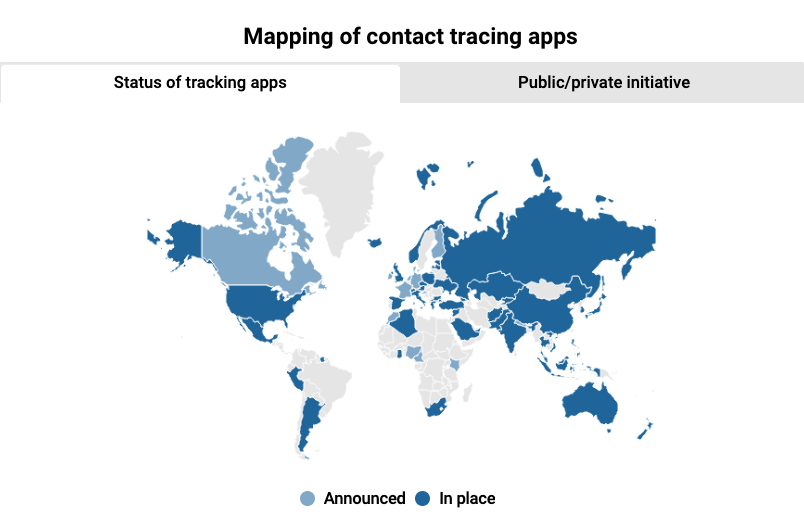

Source (including interactive chart): https://infogram.com/digital-watch-covid-19-page-mapping-of-tracking-apps-1h8n6mzre0nz2xo

As I was saying, most countries have already started developing these technologies, some of them have already rolled them out and they’re being actively used. This is a map that somewhat visualizes where and at what stage of the rollout countries currently are. So you can see, it’s pretty much all over the place. It’s not super accurate because things are moving really fast, as you know – solutions are being proposed and then rolled out or are in a pilot and then abandoned or changed or switched over to different models. So it’s a fast pacing environment when it comes to these types of apps. There are many flavours of COVID-19 apps, really. They don’t all do necessarily contact tracing as in establishing exposure between people. Some of them just do sort of symptom reporting, so people are suggested to install the apps and then whenever they feel they might have symptoms that are typical for COVID-19, then they have some technical means to report these symptoms to the authorities and to either get a sort of self-diagnosis or at least alert the authorities that they might have been infected. However, specific contact tracing is what is most interesting for us and what is really becoming the more common practice, at least in Europe. And there are many flavours of this as well. Those systems tend to do things in different ways, leveraging different types of data that smartphones are able to collect. Some collect location data, some collect even names of wireless networks in the surroundings and some decided to go for Bluetooth. In other countries, for instance in China, they’re using a different model. Instead of having contact tracing in and of itself done by apps, they’re having people install apps to check into places using QR codes. So there’s a trace history of who has entered certain buildings or other places.

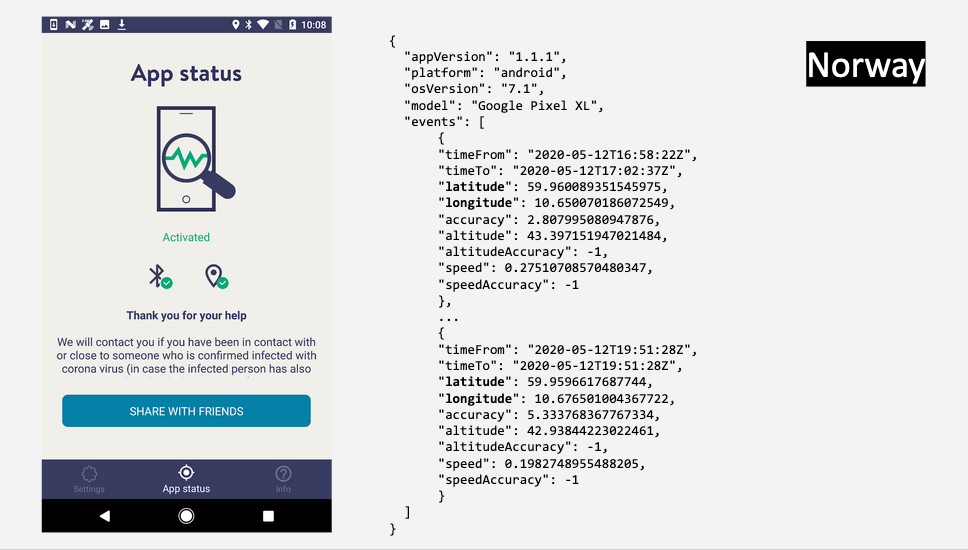

In terms of apps that actually do some sort of contact tracing using data from a phone, there are many different implementations. The ones that tend to use location data are not very popular in Europe. They’re more popular in countries in the Middle East and North Africa, as well as in other regions in Latin America and so on. In Europe, there is only a couple that use location data, so essentially GPS of the phone. One of them is Iceland, which has built these open source app, Rakning C-19. It collects a trace history via GPS coordinates of the phone at any given point in time and then stores it locally. Then the location data is only uploaded to the authorities upon request. In case the health authorities have reasons to believe that a person might have been exposed or if this person has been diagnosed positively with COVID-19, then he or she will be requested to upload their location history, so that they have an overview of where the person has been in the previous few weeks. There are other ones that are more invasive. For instance, this is an app from Norway. They primarily do location tracking using GPS on the phone as well. So you install the app, you register with your phone number, and then the app starts silently collecting location history. But in this case, instead, the location history is actually uploaded, not necessarily in real time but regularly enough, to the central authorities, so that they actually have a live view of where everybody has been in the previous, actually few minutes. So it’s quite accurate – and invasive to some degree because they are harvesting large amounts of data from people’s movements. This is very untypical for European countries, it’s actually the only one that I know of that goes to these extents. As you can see, the left side is a screenshot of the app, the right side is a typical message of data that is being uploaded by the app. Whenever it sees that there’s been some sufficient movement by the smartphone that has the app installed, they upload details on latitude, longitude and altitude, and speed as well, of the phone at any point in time.

Source: Taken from Claudio’s presentation charts.

Other apps can use location data as well, and even expose some of these data intentionally or accidentally. This is an example of an app being used in India, which is actually being rolled out as mandatory, so people have to install and use it, otherwise they’ll face penalties. This app itself somewhat accidentally exposes details over where infections are in in the country. And that caught some attention from researchers and received some critique in the media because this tracing could be reversed and used to triangulate where people are, where there are actually active infections, by sort of leveraging the access that the app has built into itself, and then you could be able to somewhat determine if, for example, there is anybody that has been infected in the parliament building or a particular address.

So there are some privacy considerations that come with the use of location data which make the issue problematic. And that’s why, at least in Europe, this model has been more or less abandoned in favour of different alternatives. The primary alternative that is being discussed and developed in most countries is to use Bluetooth, more specifically an implementation of Bluetooth which is called Bluetooth low energy, or BLE, which is basically a less resource and power consuming way of using Bluetooth transmission to exchange data between devices. Thos is a protocol that has been around for a very long time, but which was designed and developed for very different applications. It was not something meant for such a large rollout and adoption by large parts of the population. It was mostly intended for IoT (Internet of Things) devices or Bluetooth devices such as headphones, for instance, which are exchanging messages with a computer via BLE in order to tell it that it’s available. The premise of using Bluetooth for contact tracing is essentially this: Once those apps are being installed on a phone, they start broadcasting messages. So immediately after the installation they will start sending these beacons, these messages into the surrounding, not targeted at anything in particular, they’re just broadcasting, so they’re kind of sending radio messages in their proximities. Then any other device which is close enough to capture that radio message receives it, while at the same time transmitting its own. A contact is established when two devices are in a certain proximity and start exchanging information which typically an identifier. Whether a person is close enough to be potentially exposed to an infection is determined by the signal strength of the radio message itself. When your phone broadcasts something with Bluetooth, it will use a chip inside the phone to send a message and the chip will have a certain transmission power that will eventually fade away with the distance that the message travels. So the closer the receiving device is to the origin, obviously the stronger the signal would be; the further away, the weaker the signal would be. So the premise of using Bluetooth for contact tracing is trying to make an estimation of how strong the signal is that the phone has received from someone else. And if it’s strong enough, that should signify the transmitting devices close enough to you, which again can suggest that you might have been exposed to someone who has been diagnosed with COVID-19.

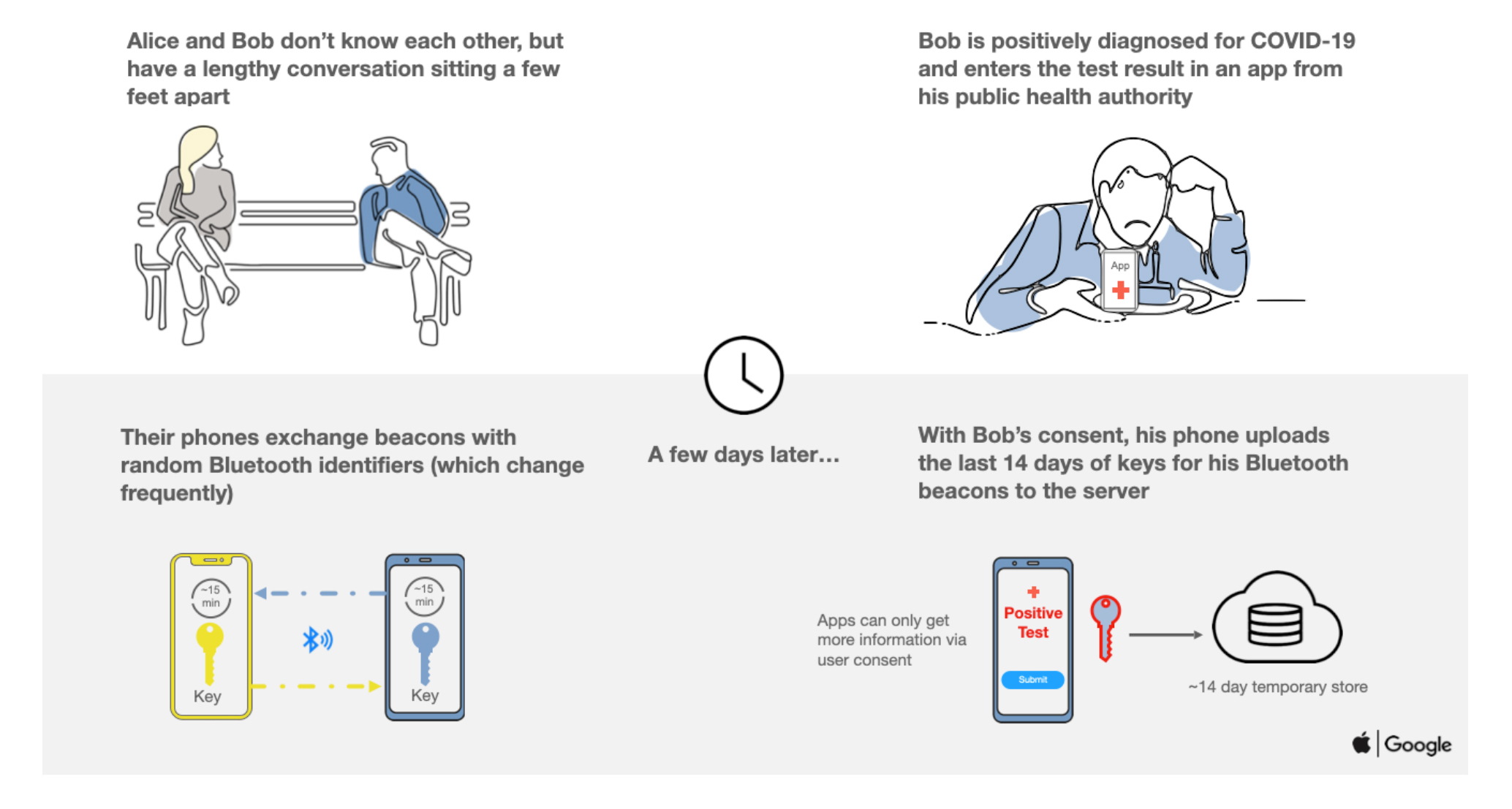

The differences between how these systems are designed is really what happens with the data after the phones have exchanged it and store them locally. What happens with this information? There are different proposals and different frameworks that have been developed over the last few months. Blue Trace is a protocol based on a BLE beaconing system that was developed by the health authorities in Singapore pretty early during the outbreak of COVID-19. And it was probably the one that sparked the whole idea of using Bluetooth as a solution for contact tracing, to digitize contact tracing. It is one of those apps that set the scene for what is being called “centralized contact tracing”. Especially in Germany, there’s been a lot of debate around whether to use a centralized or decentralized solution, we’ll get to what that means in a second. In the example of Norway, besides location data they also use Bluetooth scanning. So they also exchange messages using Bluetooth and in this particular case they exchange an identifier, just numerical strings essentially, which is provided by the service upon registration, and then the app basically just broadcasts Bluetooth messages using that identifier without ever changing it. So you could potentially track people’s movements by monitoring for specific identifiers, if you had enough sensors around the city, for example. Another proposal, which probably was one of the first one that tried to reverse the centralized model of Blue Trace and that helped sparked these centralized vs. decentralized debate in Europe, is DP-3T, which stands for “Decentralized Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing”. This was, at least at the time, considered to be the most privacy preserving way of doing contact tracing using Bluetooth, using smartphone technology in general. And then a few weeks later, Apple and Google came along with probably an unprecedented partnership, given that obviously Apple and Google are big competitors in the smartphone market. So it was quite surprising to see that, out of the blue, they decided to join forces to develop together a specification of how to do contact tracing according to their own standards and then developed essentially an API framework upon which authorities will eventually build their own apps using a protocol, cryptographic specifications and Bluetooth specifications that Google and Apple agreed on and defined. This is unfolding as we speak. They announced this, provided some public documentation and are probably going to start rolling out this functionality on our phones in the next few weeks. And then we’ll see apps leveraging these frameworks being rolled out in the weeks to come. If you’re interested in the specifications, I actually put the link here, it’s quite interesting from a technical perspective.

The way in that, in the case of Apple and Google, this system would work is essentially what they described in this graphic. Two people meet and, this is the theory behind it – we’ll see if that will work in practice –, they spend enough time together, a few minutes, and in the meantime the phones are exchanging anonymous identifiers between each other using Bluetooth. And then the apps of each of them take these messages and store them locally. Then, when one of the two people that have met would be diagnosed with COVID-19, they would go to the authorities, would be diagnosed and treated and at the same time the health authorities would ask the diagnosed patients to upload all of the identifiers that they have generated, the ones that they have transmitted, and then these identifiers would be put on the internet somewhere for everybody else to download and compare locally. So, for example, if Bob is diagnosed with COVID-19, he will have to upload all of the identifiers that his own phone has transmitted, so that later on, Alice could automatically download this data and then could check with the app “Okay, have I seen these identifiers in the last two weeks, if I have, then I need to report myself to the health authorities as well because I might have been exposed to someone who was infected.”

These different approaches are sparking the debate between centralization and decentralization of contact tracing. It is something that is heavily debated in Europe and the US, a little bit less so in in other parts of the world because there are either different solutions being adopted, for instance using GPS location data instead of Bluetooth, or because the privacy culture or privacy regulations are not the same. But in Europe, there’s a strong sense of privacy and with GDPR and recent data protection regulations there’s a lot of concerns over what could be the potential risks associated with these types of systems. While countries have started using centralized models, where all of the data is just being uploaded to a central server, many are asking for decentralized models which are more privacy preserving. At the end of the day, the essential difference between the different models is based on two main questions: What kind of data is being shared by the apps? And where is the analysis of these data actually happening? In the case of centralized architecture, for instance with Blue Trace, or the app from the British NHS (National Health Service), or the proposal from the French INRAE (National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment) – those are all centralized proposals; also PEPP-PT (Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing), which was the one that Germany was originally going to go for and then eventually abandoned a couple of weeks ago. So in a centralized architecture, the way that these would function essentially is: Apps would harvest the messages that are being exchanged over Bluetooth and then, whenever someone is diagnosed with COVID-19, they will upload pretty much all of the data that they have, both the messages that they have transmitted with their own identifiers as well as the messages that they’ve collected from other phones with the identifiers of other people. Then all of this data would be analysed in a central place, which would typically be a central server management by the national health authorities. The problem with this system and the reason why it took a lot of backlash from the privacy community and the human rights community, and even from Apple and Google at the end of the day, is that because of the fact that it centralizes so much information, it would potentially allow someone who has access to this data to start making complex analytical models on top of these data to reconstruct interactions between people. One would be able to essentially reconstruct who has been in contact with whom at which point in time and establish social graphs between people by virtue of being able to connect and correlate all of these different identifiers that people have transmitted and received. And this is, again, allowed by the fact that diagnosed patients are uploading all of the messages that have been both transmitted and received. This is concerning for privacy advocates and it’s something that has been heavily campaigned against by those that are promoting seemingly more privacy preserving alternatives. But yet, there is a strong push from certain countries to stick with this system because it would obviously give more information to the authorities, which would have more control and more overview on people’s movements in a country, which – in theory – would be useful for tracing infections.

In a de-centralized architecture, the system is a little bit different. In the case of someone being diagnosed with COVID-19, instead of uploading to a central server everything that they have both transmitted and received, they only upload the messages that they have transmitted, so only their own identifiers and not the ones of other people that have been in their surroundings. In this case, the health authorities are only able to see identifiers of those that have been diagnosed, but not the identifiers of everybody else. The analysis of the data does not happen on a central server that is run by the authorities but happens on everybody’s device. In the case of, again, Alice and Bob, If Bob has been diagnosed positive with COVID-19, he will be asked to upload his own identifiers to the central server. And then Alice would eventually download those identifiers automatically, compare them locally, so that the correlation and the determination of exposure risk is done locally on the device of every user, and then every user is given the choice of deciding whether to report anything to the authorities or not, and what actions to take as a second step.

So these are two different models. Apple’s and Google’s proposal fit into the second category. They propose a decentralized architecture. And it was a very smart move, I think, because they anticipated the move at a pretty early stage of the pandemic, but where it was already inevitable that countries would eventually demand some form of regulation which would make smartphone producers change something. And so, I think, they took the upper hand and decided to anticipate that move and to propose a framework that would work and would satisfy contact tracing requirements and, at the same time, would be as privacy preserving as possible. And this also solved some issues that I will get into in a second.

GPS location tracking systems are very invasive, they basically just give full visibility for the authorities on people’s movements, to a very accurate degree. But even in the case of Bluetooth, which is still a better alternative compared to others, there are potential issues and those issues vary in different ways, which is why there are various considerations to be made. And really, the devil is in the details, it mostly depends on how these technologies will be designed and implemented and when they will be rolled out, which will be in the next few weeks. There is an issue of privacy, of course: Are those apps going to be able to establish an identification of the person behind it? For instance, are the apps going to require a registration that will connect the app to a national ID, to a phone number or anything else that will allow for some sort of correlation or identification of users? The accuracy: Is the measurement going to be active by using Bluetooth? I’ll get to my reservations here in a second. Security: Does it further expose devices to potential security liabilities? Is the data secure – so how is the data stored and who has access to it? Are there companies or only public entities having access to this data? Could it be breached, could it be compromised, could it be leaked somehow? And then a matter of reliability: Digital systems using radio protocols could be subject to various forms of interferences, jamming, or even some kinds of attacks, like cascading replication attacks, which I think could actually be possible even in the case of Apple’s and Google’s proposal. In that case, just to give you an idea, someone malicious could set up a bunch of Bluetooth sensors around the city, harvest messages that are being exchanged in the proximities, take the identifiers of people and just rebroadcast them around the city in other places. If someone then gets diagnosed with COVID-19, there would be identifier spread out all over the city and this would basically completely nullify the viability of using those for contact tracing. This is a possibility and very unlikely to happen, but still, there are issues around this.

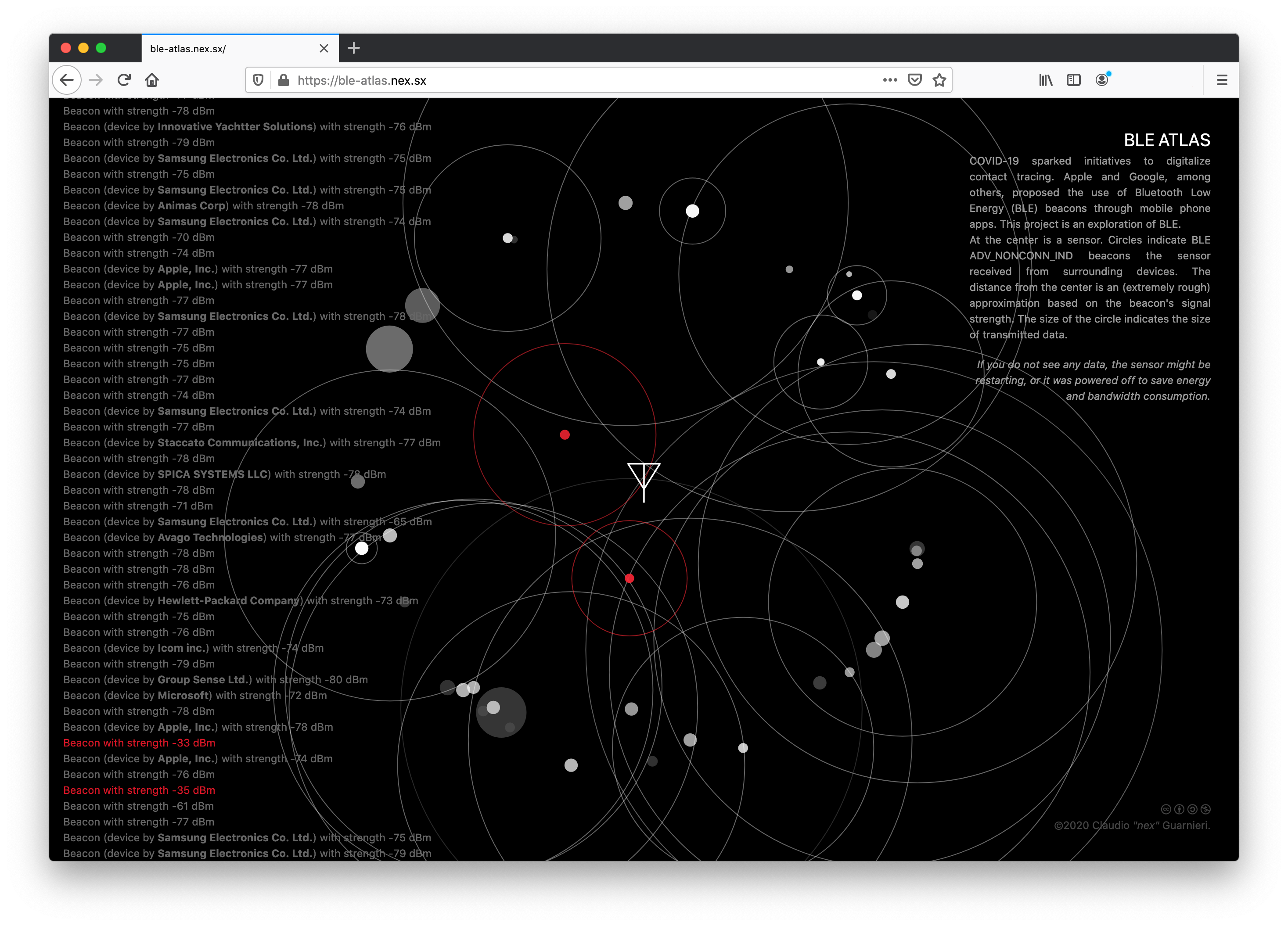

Claudio Guarnieri, “BLE Atlas” (2020); https://nex.sx/art/ble-atlas/

Because of the intensification of Bluetooth as a contact tracing mechanism, I wanted to learn better how it is this supposed to work. And how does that already look like, given that they’re trying to use a system that is already in place. So there’s this kind of little project of mine, “BLE Atlas”, which is an adaptation of my previous work, “Radio Atlas”, but specifically dedicated to Bluetooth low energy (BLE) transmissions. Specifically, a type that is in an Apple’s and Google’s proposal that would be used eventually for sharing messages between phones for contact tracing. The system I have set up is actually running from a simple computer with a particular Bluetooth device that allows me to do some more things than I would typically be able to. It is basically sniffing and recording Bluetooth messages around it. As you can see, there’s a lot of it already going on as it is active right now on the website. There is a couple of things that I noticed with this that I will get to in a second, but one of my main interest was both, to understand how this approach is working and how much noise there is, but also to signify the fact that there is a presumed locality and ephemerality of this data that comes with the idea of using Bluetooth, which is just contained to some meters of distance. If I’m just able to record it and put it online, what does it mean for things to be “local”? What does it mean “to be in my proximity” if suddenly I can transmit this to somewhere else and visualize a website, or even do something more with it. To me, this is both an experiment as well as a way of doing a media critic of Bluetooth as a means for contact tracing, reversing the assumptions behind the technology itself. The first thing I’ve learned is, it’s a very crowded space. As you can see, these are all beacons that my device is currently detecting. And this is even just a subset of the actual number because it would be way too much to visualize in the browser; if I were to visualize literally all of them it would be way too slow. On the left side you can see all of the beacons that it receives, if it is able to identify what type of device it receives then it also tells the manufacturer, Samsung, Microsoft, Intel, Apple etc. On the right it says which strength and then a number in dBm, so that is the numerical value of the signal strength of this transmission. That number will be the number which will be utilized by these apps in order to determine if I’ve been exposed to someone who’s been infected. These values tend to range between minus 30 to minus 90, depending on the strength of the signal received. In this range, essentially, they’re trying to make an estimation of what does this translate into meters or into centimetres, essentially. The visualization is putting a dot for each beacon. They’re all somewhat at an average distance because there’s literally nobody around me right now for several meters, but the signal strength is still quite high.

One consideration that I have made is that it’s an extremely crowded space. The other is that I have serious reservations regarding the accuracy of Bluetooth as a means to do in distance measurement for contact tracing because of the fact that being a radio transmission, Bluetooth is subject to environmental factors. First thing first, the app is not able to determine whether there’s anything between me and the person transmitting. So if there’s a wall, the app doesn’t know that there’s a wall between us. If there’s a window, the app doesn’t know that there’s glass between us. So there’s already an issue that could cause false negatives. Also, the app doesn’t know the conditions in which it is in and what could affect positively or negatively the strength of the signal that is being transmitted. So let’s say that you’re in a park with literally nothing around you that could cause any sort of interference, there would be less, say, damage on the quality of the transmission and so it might look like you’re at a closer distance to someone else in the park who’s using the app then you actually are. At the same time, if you have, for instance, your phone stuck in your backpack, and if the backpack is stuffed with things, the signal strength will be heavily reduced because it cannot really penetrate a whole lot and it might make it look like you’re actually at a further distance than you really are from another person who’s literally right next to you. That would cause also issues of false negatives. This is why I’ve reservations because it is extremely approximate. It’s taking a measurement, it’s taking a number that is not intended to approximate distance – it’s only intended to approximate quality of service – and then estimate how far away someone is. Interferences and malfunctions are inevitable. If you look at some other Bluetooth apps, there are people leaving complaints in the reviews of the Google Play Store pages and the App Store pages, lamenting for instance that their Bluetooth headphones are disconnecting all the time, and that the phones actually stop transmitting when they go to sleep and all of these issues.

This is also extending beyond just national contact tracing. There are companies starting to develop Bluetooth based contact tracing systems that are targeted at businesses, so that for instance, companies or universities or whatever could enforce people to wear Bluetooth transmitting devices such as bracelets in order to track interactions between people. There are issues beyond the pure technical ones, such as a number of human rights considerations. Those are the ones that make it important for us at Amnesty International to look at this critically and analytically. Firstly, these technologies are being rolled out super quickly and without proper testing. So we don’t really know how effectively are these going to work. And because of the fact that there is no previous history of similar circumstances, in terms of a global pandemic combined with an attempt to digitize a response to it, it’s very hard to actually tell if this is really going to work. But in order for us as human rights activists to justify this sacrifice of people’s right to privacy, there needs to be measurement of necessity and proportionality. That’s truly what we ask every time, whenever there’s a state that is demanding some additional powers when it comes to infringing on people’s rights. And in the case of the right to privacy, even by international human rights law, there are concessions that can be made to states if they prove that these measures are necessary and proportional. These considerations need to be made in each and every case, and so in this case the properties need to be proven and tested as well.

Other concerns that we have besides issues around privacy of users is the potential discrimination factors that these apps could unintentionally bake in. For instance, if apps that start collecting this data would then allow this data to be used to calculate risk scores and then these risk scores would be used for additional purposes other than just COVID-19 tracing, for instance for insurance purposes or access to public services, health care, and even access to work and many different aspects of life, there could be issues of discrimination, especially for more marginalized parts of society, for example people that don’t have access to technology as much as others. For us it is very important that these technologies, if they’re proven useful, still need to come along with an equitable sort of access to health care. And these apps must not become a determining factor whether someone shouldn’t be prioritized as a patient in a healthcare system, because otherwise it will inevitably extend the digital divide, not just in terms of access to information and access to technologies but also in terms of access to healthcare.

Some experiments are still going on in, for example in Iceland. They are actually being sceptical right now with the results that they’ve had in using location data. We’ll have to see how things unfold in the next few weeks. For sure, these apps will start being rolled out in the next month or so by most European countries. And with that, I conclude and leave a couple of minutes for questions.

Linus Ersing: Despite the now decentralized angle most of the developers pursue, you already mentioned that there are a lot of workarounds that allow for the identification of app users. People don’t want that, obviously. Is there a realistic possibility to prohibit such workarounds? Maybe someone can release a catalogue or some sort of checklist for users to make them aware of possible pitfalls using these apps. Or is something like this already happening? Enabling a bottom up literacy for users?

As it stands, the bottom line is: I think that the most privacy preserving and the most promising proposal there is at this point is the one from Apple and Google, along with DP-3T, which has some minor differences but is essentially using the same underlying architecture. The essence of the problem will become more clear at the point where actual apps are being built on top of these things. Until we have examples of apps that are being rolled out leveraging the systems, it will be hard to tell exactly what will be the specific privacy implications of each and every one of them. So we somewhat will have to wait and see. If people will respect the specifications from Apple and Google accurately and will not break out of that framework, the possibility to identify people of that system itself will be very limited. But it really depends on what additional steps will app developers take on top of that system. I don’t think there can be an answer to this yet. Because implementations are still not public in most countries. The ones that are already public are problematic to compare. And most of the ones that are public, again, already do a form of identification of people. The ones to come will have yet to prove themselves. So I don’t really have an answer right now because this is sort of a developing issue.

Antim Gelew: Could you say what effects will the implementation of these apps have on our future society, generally speaking? And what will happen to these apps when the COVID-19 crisis has past?

That depends on what we’re going to allow it to look like. One of the core demands that we at Amnesty International are making is that these apps, if they’re necessary and proportionate, need to be time-bound. So there need to be legal assurances that, at the point when the COVID-19 crisis is over, these apps will stop working and the data will be eliminated. That’s definitely step number one, they can’t continue on existing without a strong, proven need from a public health perspective. I’m sure it will have some lasting effects just because of a general change of culture. And not necessarily just in Europe, but even thinking more globally. And I spent more time actually looking at apps from other regions of the world, not necessarily in Europe, but for instance, in the Middle East. And the level of intrusiveness of some of these apps is quite remarkable. The problem that I see is that they’re being adopted in large numbers because they’re sort of bought into by people in a moment of emergency and crisis. The acceptance of more privacy violations will inevitably have some lasting effects. I couldn’t have imagined apps like these having any success or any foothold in our societies five years ago, where there was a strong debate on surveillance and privacy. But now things have changed and this will for sure have effects. But the best thing that we can do is look critically at how these apps work and demand strong regulations and oversight.

Daniel Irrgang: In one of our last seminar sessions we discussed the surprising acceptance of contact tracing apps, surprising especially from a perspective of critique of surveillance technology, by consulting Naomi Klein’s claim of the “Shock Doctrine”.* Do you see a parallel between these type of strategy and current issues around the COVID-19 crisis?

* Framed within her critique of Milton Freedman’s neo-liberal paradigms, Naomi Klein describes the shock doctrine as a strategy of “using moments of collective trauma to engage in radical social and economic engineering.” – Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine (Knopf Canada, 2007).

Absolutely. But it’s also very contextual, locally. One thing that I find very interesting is looking at Scandinavia. Sweden is so far outright refusing to have any sort of contact tracing solution implemented because the general kind of agreement is that they would be not useful enough and too invasive into people’s privacy. But at the same time, you have Norway, which is right next to Sweden, which is doing the exact opposite. They have fully embraced a, compared to Sweden, quite invasive system that literally just tracks people’s movements as they go around their businesses every day. There’s some interesting sociological analysis to be extracted from this as well, since the acceptance of this technology is probably rooted in people’s culture and national identity. It’s a fascinating time, but also a slightly concerning one.

Greta Brungs: I also have a question. Actually, it’s two questions. What do you think will be the approach of the German government to make people use the app? Will it be just that, that you can use it if you want to and that authorities hope that enough people will use it? Or will it be like in India, for instance, forcing people to use the app?

Germany first went for a centralized architecture. Then they abandoned that and decided to probably go for the Apple and Google model eventually. So that’s, I guess, a positive development in terms of the incentive for people to use this. This is the main reason why, personally, I suspect that a lot of these efforts will be not as useful as people hope them to be. Because so far, even in places where these apps have already been rolled out, the penetration has been much below the expected rate. So as I mentioned at the beginning, statistically they would shoot for a 60% adoption rate in a country. While currently, in most countries using such apps the rate is still below 20%. The way to address this issue will change from country to country. I don’t think Germany will enforce it as a mandatory measure because it would be heavily criticized and campaigned against. Actually, I don’t think in any European country we will see these apps being enforced as mandatory. Because there are so many issues that come with making this mandatory, such as infringement of people’s right to privacy and freedom of association, freedom of expression and so on. But also, because making it mandatory will almost necessarily add an element of discrimination baked into them. And the moment that you start making this thing mandatory, I think you start pushing away people from feeling confident and comfortable using the app. I think the more successful strategy would be to be as transparent and open as possible. Make solutions that are privacy preserving, that people don’t feel are too invasive or infringing people’s rights to privacy – especially in a country like Germany, which I think has a pretty developed sense of the right to privacy. And make sure that this remains a voluntary measure that people feel participating in, rather than being obligated to do so. But that’s my personal speculation.

Daniel Irrgang: One major argument of the political players, at least in Germany, is exactly this, if the app will come, it will be voluntary. But then there are critical voices against the “voluntary” argument, stating that there will be a huge peer pressure, as in “everybody is using the app and you are not, so you are acting socially irresponsible”.

Yes, it’s a matter of voluntariness in legal terms. But is it really voluntary if there are incentives or penalties? It might be the case that the app is not mandatory to install, but those that actually choose to install it, get some advantages. Then it is not really voluntary, then it becomes a matter of not just peer pressure but in some cases, in certain segments of the society, it becomes effectively mandatory. If installing the app will give you certain advantages or a lenient season in your health insurance costs or things like that, at that point certain segments of society will have necessarily to join in in that effort, because of the fact that otherwise it becomes an economical cost. And when it becomes an economical cost, there is no real voluntariness anymore. In our campaigning, for instance in our messaging and guidelines that we’ve been publishing and provide to states, we exactly say this: These apps need to remain voluntary, and they should not come with incentives or penalties. So it’s a matter of acceptance, I think. And the fact that the success of these apps is reliant upon not just the accuracy of the technology itself, but whether this will be imposed upon people, I think it’s more a sign of the limit of this technology rather than of the opportunity that it provides. But again, it’s also a cultural thing, and every country and every population is taking it very differently.

Greta Brungs: You said that it was kind of a positive step by the German government to detach from the centralized idea and to consider the app by Apple and Google. But my question now is, isn’t it critical having huge private companies like Apple or Google provide an app like this? Or is it just a decision dictated by the situation, as it would be nearly impossible developing an app like that by a governmental institution within such a short period of time?

That’s a very good question. There are a couple of aspects to consider. Firstly, to be clear, Apple and Google, so far, are not going to provide an app. What they’re going to provide is a framework, essentially an API, on top of which national authorities will be able to build apps. So they’re not going to be able to control data, as far as the specifications go. They’re essentially just opening and accessing the operating system in order to facilitate the development of contact tracing apps. But they will have to respect the model that they’re defining in the specifications. In the current proposal, the data that is harvested by national health authorities through these apps that are built on top of the API would be under the control of the national authorities themselves. The apps will upload data to what Google and Apple are calling a diagnosis server, which will be operated by the country itself. So as it stands, the companies are not necessarily going to have access to sensitive information, in relation to these particular apps.

There’s also an issue of reliability. If you take, for instance, the case of the app in the UK: The UK has, and that’s already open source, an app of their own, which uses a centralized model. And it is quite likely that they’re going to abandon it as well and switch over to Google and Apple. I don’t think that’s necessarily the case because of the fact that they suddenly have a change of mind and want to go for a decentralized architecture. But quite simply because building apps that are using Bluetooth in these ways without using an access that is being specifically provided by Apple and Google for this purpose is extremely not reliable. As I was saying earlier, on iPhones, for instance, apps are not supposed to use Bluetooth unless they’re being actively used by the person. So if you have an app open with the window open, then the app is entitled to use Bluetooth. But then, if you switch it over and start looking at Twitter or whatever else and the apps switches to the background, then access to Bluetooth is actually being cut out from that app. So there’s a technical limitation in the way that this can be implemented without having Apple’s and Google’s contribution. That’s one of the reasons why they opened this. Most of these apps that you’re seeing, including the one from the UK, they develop, they’re suddenly in a pilot and during the pilot they realize that it’s extremely unreliable, because of the fact that the apps just stops transmitting eventually, or they cause malfunctioning with other apps or other Bluetooth devices and so on. Because essentially, they’re using Bluetooth or BLE in a way it wasn’t really supposed to be used. Other proposals are going against the original design of the operating systems on which they’re supposed to run. And so I think they will eventually switch over to these companies’ proposal, just as a matter of making the apps functional and not buggy and crashy.

At the same time, it’s a matter of sovereignty that is being particularly debated in France, as France is heavily resisting Apple and Google. This is a matter that extends beyond the specific issue of COVID-19 and opens up debates around national sovereignty and how does that translate with technological sovereignty – in a reality where nearly all of us are using devices that are being built by a couple of American companies, which essentially can decide how these devices are supposed to work. This is in contrast, in conflict with national authorities which have decided that they have a technological need, but which does not necessarily fit to the choices that these companies are making. So it’s becoming an interesting “countries vs. multinational corporations” conflict. But that’s more a political and philosophical issue rather than a practical or privacy issue.

Greta Brungs: I feel like that the German government detached from the centralized idea because of Apple saying that they will not make it possible to have an app running Bluetooth in the background.

It’s actually not possible. So it never was possible, even before the pandemic. This was a deliberate design choice for both security and safety purposes, as well as for reliability reasons. The inability of apps to continuously do Bluetooth scanning, as it stands without using the new API from Apple and Google, is something that has been in place for years. Because, for instance, on iOS they want to prevent apps from interfering with other apps that might need to be using Bluetooth at the same time, as well as preventing potential security issues and attack surfaces that come with apps that are broadcasting continuously. So it’s not something that companies are preventing now and do something different instead, it just was always there. Now, suddenly, the countries that are developing centralized systems or apps that are using Bluetooth but not with these specifications are facing the existing technical limitations of the platforms that they are trying to use. And Apple and Google offered an alternative, which comes with very strict conditions. I think they’re trying to take the middle way of facilitating something to happen without coming across as they would contribute to privacy invasions of their users.

Daniel Irrgang: Allow me one last question, a kind of crucial question, but maybe it’s also a very general one. As you said, apps can only work complimentary within the proper health care system. Do you think that contact tracing apps, BLE beacons or otherwise, will actually work, technologically and socially? Or are such initiatives simply a case of techno-solutionism, to use Evgeny Morozov’s term, which is the “Californian” passing on of social problems to yet another technology?

I think these apps are to be considered an experiment. And personally I feel that this experiment is probably not going to yield the results that many hope. I think that it is highly likely that these apps will not be particularly useful in the COVID-19 containment measures, and that they will be an additional add-on, which, however, will not be of substantial influence, positively or negatively, in the way that things will go. And I think this for various reasons. In particular, because I don’t think they will get to a substantial adoption rate in most countries. And I feel that the more these things will be used, the more the issues will be evident to both users as well as to developers themselves. At the moment where they will start having unmanageable numbers of false positives and false negatives, which is a possibility – I’m not saying that it’s necessarily the case, but it’s a possibility that comes with having a technology that has not been thoroughly tested, especially not tested against all possible circumstances and scenarios –, there will probably be some issues. And by the time that these issues will be resolved and fine-tuned enough to be accurate, we will probably be at a quite late stage of the pandemic. So generally speaking, I feel that practically it’s not going to be a very useful measure. The other consideration is that it’s going to become more of a matter of giving an instrument to people to feel more confident in resuming their normal daily lives. And that’s something that is very easy to do with technology. It’s something you buy, install and then suddenly that serves a purpose. For how inaccurate that purpose is or how unreliable that purpose is, it will still probably serve the function of giving some confidence back to people, who suddenly find themselves having to resume their previous life in a very different world, in a very different context. So there’s more a psychological effect to it, I guess, than a practical one. In terms of COVID-19 management, let’s say, I’m very reluctant in being too confident of the success of these experiment. But it’s an inevitable one. So it’s something that we’ll have to go through and see how we will come out at the end of it, and it probably will not be the last one. When these practices are being established, then we might see these things resurface again, in case of a second wave or in case of a different kind of health emergency, which might not be COVID-19 but something different. I think it has just not been enough time and empirical experimentation to really get this right at the first goal.

Thank you, Claudio, this is a fitting closing comment, since it animates us to keep on thinking about these issues. Thank you so much for your time presenting and discussing your current work with us. And thanks to all the participants for their stimulating questions.

Thanks for having me and have a good day!